![]()

The end-of-June late-morning sun promises to fry the brains of the assembled Who’s Who of international opera critics. No one dares though to leave the press conference in the cloisters of the Théâtre de l’archevêché until we deal with what we are here to discuss, and that is not just the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

The end-of-June late-morning sun promises to fry the brains of the assembled Who’s Who of international opera critics. No one dares though to leave the press conference in the cloisters of the Théâtre de l’archevêché until we deal with what we are here to discuss, and that is not just the Festival d’Aix-en-Provence.

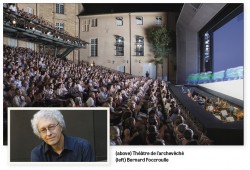

So we wait, as a trio of officials fills the shiny air with bright promises of newly re-imaged old work – Mozart meets Mussolini in Così fan tutte to open the festival’s 68th iteration – and as company director Bernard Foccroulle, frazzled-looking most times yet now cool as a glaçon – extols outreach programs, “school support,” administrative breakthroughs … We wait, plastic water bottles draining as steadily as the temperature mounts. Then: “Brexit.”

The word, spoken not shouted, came from out of nowhere – maybe from Foccroulle himself? Or who knows? It didn’t matter. It was as if a code had just been cracked; a world of information started spilling out.

The “British exit” was inevitably the talk of this European summer, its implications growing thornier with every new detail. For this assembled music crowd, the very thought of the United Kingdom’s decision to sever all ties from the European Union (EU) was a stark reminder that unfettered border crossing has been to opera’s advantage, long before Handel took his act from Halle to London.

Bottom line: if there’s a Brexit-induced clawback of arts funding in Europe or a redistribution of funds, the shrinking effect will be felt soon enough worldwide most particularly when it comes to operatic co-production.

For opera and theatre in England, minus the 16 percent of its budget originally from the EU, it will mean a “great sadness,” Katie Mitchell, Aix’s genius-in-residence, chimed in from somewhere behind Foccroulle at the festival-starter press conference. (Note: the formidably stern Mitchell, frequently called Britain’s “greatest living director,” has worked mostly away from England the past few years. Her introspective take on Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande is likely to be one of this festival’s two legacies.) Brexit pushes the EU-needy English National Opera even closer to the brink of collapse, if that were indeed possible (although some fightback came this summer by way of the company’s Tristan und Isolde, with sculptor Anish Kapoor’s sets drawing much of the attention).

The more the talk continued, the more the sense of worry grew. What, for example, would Brexit auger for the broader reaches of the co-production ideal of the sort that has the Canadian Opera Company bringing Richard Jones’ Aix debut production of Handel’s Ariodante to the Four Seasons Centre, October 16 to November 4 this year, a co-production with the COC, Dutch National Opera and Lyric Opera of Chicago? (As a matter of interest, the record, going back to the 2006/07 season, shows that the COC has presented 19 co-productions including this year’s October 6 to November 5 Norma, directed by Kevin Newbury, a co-production with San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago and Barcelona’s Gran Teatre del Liceu.)

And what will Brexit mean for an Aix festival that’s arguably the world’s centre for international musical wheeling and dealing? Foccroulle looks less than happy at the thought. “Artists need to travel,” he tells me after the press conference. “And for opera it is crucial to work with other cultures, other languages, other ways of producing art – also to be in contact with other disciplines. How much is dictated by the European Union? Well, a lot is facilitated by it, supported and subsidized.”

If any torpid Mediterranean city can be described as go-go, it’s Aix. The city downtown has its share of timeless moments. Cours Mirabeau, the coolest summer-strolling corridor this side of Barcelona’s La Rambla, is lined by a row of former grande bourgeoise homes on the south. Some are now banks. Here and there are any number of nearby ornate fountains – “Aix” comes from the word for water – such the Baroque Fontaine de Quatre-Dauphins where dolphin-like gargoyles spew water (not a quartet of future French kings, as the fountain’s name might suggest). This is not to forget painter Paul Cézanne’s airy studio that’s an obligatory visit for every bus tour heading north of town.

Aix’s cultural clout has been on the rise pretty much since the festival’s founding in 1948 as home for Mozart aficionados. It’s a photography and arts research centre. The festival itself can now brag about 97.9 percent full houses for opera and slightly over 94 percent for the many concerts. Otherwise Aix is France’s version of Silicon Valley with high-end university research facilities and credit card microchip processing plants edging their way out into some of the best olive-growing hectares in all the South of France. (“There are a great many wise people there” was written into the founding act for the Royal University in Aix, 1413.)

Translated: this means money. Elsewhere, to describe anyone in the arts as a “money person” might be an insult. But not in Aix and not when it comes to Foccroulle who also happens to have led Brussels’ La Monnaie for the past decade and a half. Foccroulle, leaving the

festival after the 2017 season, is the king of co-production, with Aix connecting opera academics from Ghent’s LOD muziktheater to the Polish National Opera in Warsaw, and with a good half-dozen co-productions on the bubble at any given time. Pierre Audi, of the Dutch National Opera in Amsterdam, will have a lot on his plate when he takes over Aix in 2018.

Foccroulle’s most lasting accomplishment – and his most audacious manoeuvre – may well lie in resetting Aix’s compass from North to South, a reset requiring a lot of creative thinking. (Cairo was a significant Aix connection/collaborator this year.) Foccroulle may be further emboldened in this decision by the recognition accorded to Aix's longtime nearby bigger coastal rival, Marseille, as European capital of culture. It seems the European south is now more than boule-playing by old guys. (Picking Marseille evidently preceded the debut airing of Marseille, the French-made big-city corruption yarn – on Netflix in Canada – barely kept alive by the bulky genius of Gérard Depardieu.)

How do we integrate opera into a world where globalization is changing everything? Foccroulle asks himself. “We have to open the doors to other cultures,” he answers. “That’s the reason for [Moneim Adwan’s] Kalila wa Dimna and for our Mediterranean program.”

Like Aix, other major European arts festival such as the Edinburgh Festival and the Holland Festival, both starting in 1947, were post-war efforts to better unite Europe. Foccroulle sees beyond that.

Like Aix, other major European arts festival such as the Edinburgh Festival and the Holland Festival, both starting in 1947, were post-war efforts to better unite Europe. Foccroulle sees beyond that.

“When I arrived here ten years ago, I was often asked what was the identity of the festival,” he tells me. “They were expecting me to answer in terms of programming of directors and so on and so forth. I think our role however is the big mutation of the role of opera in a global world. That means doing many things to open doors for living artists. In Italy, for example, young artists, young composers and directors have nothing to do because the Italian opera houses don’t offer them anything. The older generation does almost everything. We also have to open the doors to other cultures and to regenerate opera through new forms.”

In keeping with this southern strategy, for his Così fan tutte French film director Christophe Honoré has re-imagined Lorenzo Da Ponte’s 18th century Neapolitan comedy as a grim Fascist parable set in the Italian-run Eritrea of the late 30s. Remarkably, the grumbling after the opening was that Honoré didn’t push the malevolent comedy as savagely far as it could go. The Trump effect?

Back to Katie Mitchell’s Pelléas, the opening of which saw a less-than-full house (which did, however, include Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund). The work is already being described as her masterpiece – the true successor to her 2012 international hit, Written on Skin, by George Benjamin and Martin Crimp. But for this to play out, in my view, future co-productions of Mitchell’s Freudian dreamworld where its secrets are about more secrets, will require considerably more orchestral oomph than was provided by Esa-Pekka Salonen leading the Philharmonia Orchestra. They will also have to find a Mélisande with some of the daring physicality, aggressive sexuality and exhilarating singing Canadian soprano Barbara Hannigan brought to the role in this production. Aix’s reputation at being good at money may be facing some challenges. Its reputation for great casting remains intact.

Aix's Axis

North-South Reset

Katie Mitchell’s mysterioso production of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande will probably emerge as the mainstream signature work from this season’s Festival d’Aix-en-Provençe. But the production mostly likely to have reverberations far into the future is Kalîla wa Dimna by Palestinian composer Moneim Adwan.

As a bilingual chamber opera in French and Arabic based on an eighth century translation of fables by Persian poet/scholar Ibn al-Muquaffa, everything about it is a world-first, we’re told. Yet there’s nothing new, or never-before, about its accessibility. Told in flashback by Kalîla (the Hawaii Pacific University-trained contralto, Ranine Chaar, at Aix), the story of a manipulated despot driven to violent extremes has a contemporary feel by way of the libretto by Fady Jomar and Catherine Verlaguet. Dimna (sung by Adwan himself) is a young hotshot on the make, a human jackal – toy animals are used in fetish fashion as narrative illustrations – waiting for the low-hanging spoils of the back-stabbing intrigue he creates.

A sense of nondescript modernity was conveyed by the sets by Eric Charbeau and Philippe Casaband; Nathalie Prats’ lumpen costumes were equally unimaginative. So visually, this Kalîla won’t change the world. No matter. Adwan’s score elevates everything to another level. Accompanied by an onstage quintet led by conductor/ fiddler Zied Zouari – an electro/groove player on his own time – Kalîla wa Dimna offers one of the most impressive melds of Middle Eastern melismas and straight-up western tonality I’ve come across.

So if a category needs to be found for Kalîla it might be filed under “folk opera” – closer to Béla Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle than to George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, please – or as important “regional theatre,” as COC director Alexandre Neef characterized it to for me shortly after he’d seen it at Aix.

The festival has gone in this direction before only last year with Serbian-Canadian composer Ana Sokoloviç’s Svabda (Wedding) which like Kalîla was offered at the festival’s Théậtre du Jeu de Paume. Opened only a few years back, this jewel-box space is found tucked away around the corner from the Musée Granet, an exceptional mid-size gallery that can trot out A-list Cézannes or Picassos whenever pressed to do so, which is never enough.William Christie’s Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria was an earlier success at the Jeu de Paume.

Kalîla wa Dimna wasn’t meant to stand alone this season. The world premiere of another cross-cultural Aix commission, Czech composer Ondřej Adámek’s Seven Stones was on the festival’s early schedule only to be “postponed” at relatively the last moment according to a festival spokesperson, “mainly for budget reasons to avoid taking financial risks. This should allow the festival to also find additional co-producers.” (As it is, Seven Stones has enormous cross-cultural possibilities as the story of a mineralogist who goes on a worldwide search from Europe to South America for the single stone about to be hurled at the woman saved by Christ after being accused of adultery.)

Only days after the Kalîla wa Dimna premiere, Lyon Opera, only a few hours up the autoroute, produced its new Abduction from the Seraglio, by Mozart, with new dialogue by Wajdi Mouawad, the French-Lebanese writer/director intended to rethink the work’s burlesques of Muslim Turks.

“You have to constantly redefine what you are, especially as a large organization,” Neef went on. “You don’t give up your core. You do what you do best. And there’s always a temptation to run after the next thing. But you don’t just keeping doing what you do. I was very fascinated with Kalîla wa Dimna. I was taken with the storytelling. In Canada we have a wide indigenous population and we have not told their stories in a big way.”

Ariodante auf Orkney

Jones’ punky production, which premiered in 2014 at the Aix Festival, goes whole hog, er, whole sheep, with this Orkney claustrophobia vibe. Besides excess tartan there’s lots of wallpaper. “What made my mind up about the production was Jones’ idea to move the setting from Scotland itself to the Orkneys,” says COC general director Alexander Neef. “He turns it into an even more remote place. Handel thought Scotland itself was a remote place.”

The new setting is Scotland of the recent past, where the heroine, Ginevra, suffers mightily to be with the man she loves, Prince Ariodante – British mezzo soprano Alice Coote, a Jones favourite, for the COC performances – only to be accused of being unfaithful to him.

“The story is wintry,” Jones tells me enthusiastically on the phone, his tone anything but wintry. “The music is baroque but the setting is 1970s Scotland. There is a tension between the two. People look at it more acutely because of that.”

Besides tension we get lying, cheating, the hero’s attempted suicide and lots of knitwear. How much fun is that? Well, lots actually. “Yes, there is this sense of melancholy that is found in many pieces of the period which I find intoxicating,” says COC music director, Johannes Debus. Despite a childhood spent as a pianist/fiddler in Baroque-rich West Germany, he’s making his Handel-conducting debut with Ariodante. “There is a lushness to the score. Opera at his time was an entertainment at an extremely high level; an entertainment is a form to allow you to forget your daily life.”

Debus was born in 1974, the year David Bowie released Diamond Dogs. Rock is not foreign to his musical thinking: his understanding of it will not likely inhibit his still-growing reputation. Ariodante, produced in 1735, was the by-product of an aggressive new marketing venture by Handel which would have made Andrew Lloyd Webber proud. In 1734, Handel moved his company from the Haymarket’s King’s Theatre to John Rich’s Theatre Royal, newly installed at Covent Garden, to find a better location and a company with a chorus and dancers. (Speaking of location: along with the COC and Aix, this Ariodante is a co-production with the Dutch National Opera and Lyric Opera of Chicago.)

“Handel always had dancers in mind: this music itself was based on dance, the sarabande, the gavotte and the bourée,” Debus continues. “Baroque music uses words the way rock does: there is always a certain rhythmical aspect to them. It’s an expression of youth. And there is the aspect of popularity in the music itself. The singers at the time were all pop stars of the period, idolized by everyone. When people went to the opera then it was not as it is today. They chatted. They might have sung along to the music. There was no holy, sacred atmosphere.”

Ariodante’s Aix debut was interrupted by France-wide strikes by arts-related workers fearful of cutbacks in their benefits. One British singer had her entrance blocked by “about 40 protestors who were blowing klaxons.” By then though, the current Handel revival – one to rival the composer’s last period of rediscovery in the 1920s – was in full swing. “I was a latecomer to Handel,” COC general director Alexander Neef admits, “but once I rounded that corner I saw him next to Mozart and Verdi.”

The Aix success this season of Krzysztof Warlikowski’s young and restless take on Handel’s Il trionfo del tempo e del disinganno, confirms what Jones and Debus believe is Handel’s intrinsic connection to today’s popular culture. Handel wrote for the street and his own generation. Il trionfo, Handel’s first oratorio, was written when he was just 22.

Jones himself comes to Ariodante through the prism of pop not opera seria. The formulaic courtliness observed by Handel’s characters and understood by his audience is not replicated in Jones’ direction, although his characters, turning themselves into manipulatable puppets, are looking for motivation from somewhere. But where, the TV? The movies? Today’s sitcom, not George II’s 18th century court, informs this Ariodante.

Maybe this hardly promises the signature shock and awe involved in some of Jones’ earlier productions like his recent grit‘n’grimy version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, his Royal Shakespeare Company debut, which had him labelled a “vandal.”

Believing that “theatre and opera are marginal to most people,” Jones says, “I am selfishly willing these great works work. And I am trying to work with people who can stimulate.”

Debus is on board with that. “I cannot say I have a vast experience with Baroque music although I’ve conducted it here and there and one of my favourite composers is Bach,” he says. “At the end though, no matter how much you do research on how the music may have been played at the time, in the end it’s the interpretation that makes the music work. You have to have someone with the right instinct for the music and the vastness of the emotion there. The result can be a very lively performance that also touches you.”